A GIS exploration of the political geography of the Holy Roman Empire

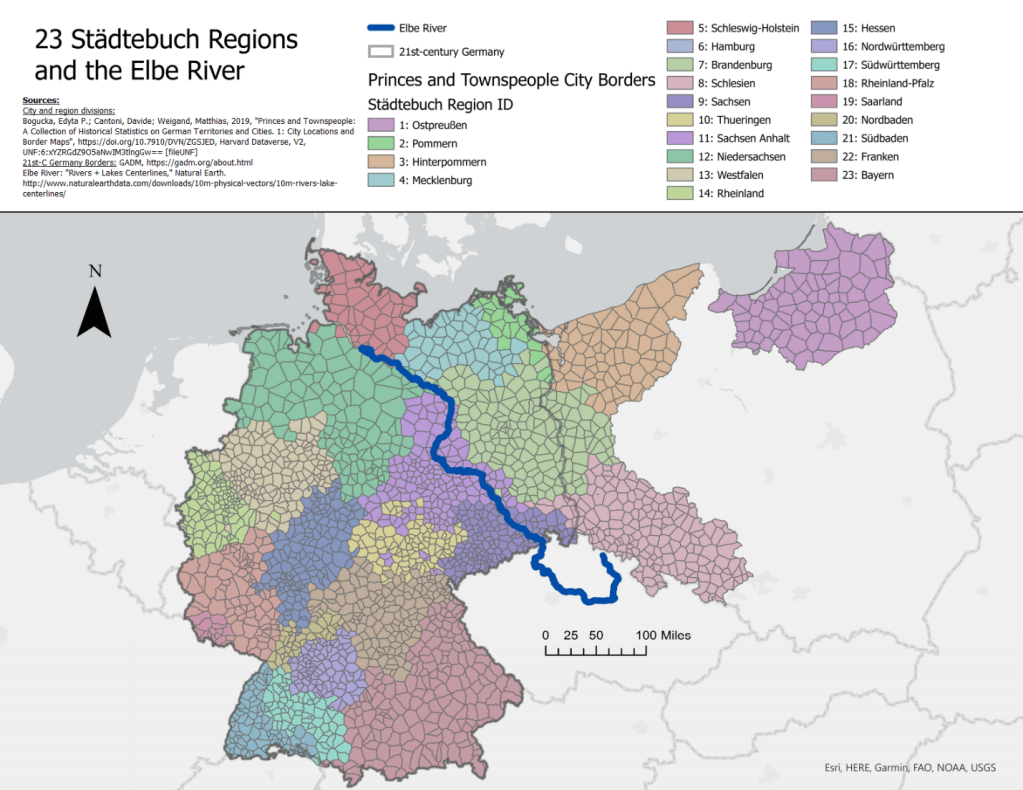

In this paper, I begin by broadly defining political-geographic patterns across the thousand-year history of the Holy Roman Empire (c. AD 800-1806). Because my interests in the Holy Roman Empire (hereafter, HRE or Empire) are quite broad both geographically and chronologically, I intended from the outside to use this project as a chance to explore the relationship between data and historiography across the Empire’s spatiotemporal expanse. Many of my maps and ideas did not make it into the final project,[1] but the experience of creating these was quite valuable nonetheless. As the paper proceeds, I gradually home my focus in on settlement patterns in the 12th through 14th centuries in the regions of Germany northeast of the Elbe river, and the south Baltic coast beyond. Throughout the writing and GIS processes, I encountered a number of historical trends that interested me greatly, and which will emerge throughout the paper.

The structure of the Holy Roman Empire naturally frustrates a study of its political geography. Whether we look at the top level of the Empire’s territorial holdings (e.g., kingdoms, duchies, archbishoprics) or at the atomic level of its thousands of constituent towns, the answer is the same: there are no hard and fast rules. This murkiness is only enhanced by the empire’s extended temporal duration, as, by some metric, the Holy Roman Empire endured from Charlemagne’s coronation in A.D. 800 to its formal dissolution in the face of Napoleon’s advance in 1806. The data in this paper comes from an ongoing study, “Princes and Townspeople” (2019-present), led by economic historian Davide Cantoni and drawing on work from scholars Brown University and the University of Munich. “Princes and Townspeople” works with city records in the Deutsches Städtebuch (Keyser et al., eds, 1939-2003, “German City Book” in English), a comprehensive[2] record of towns and cities in Germany from Roman times to the late 19th century. The team’s datasets include transcriptions of much of the record from the Städtebuch, combined and cross-referenced with the current scholars’ historical and spatial research. The data features information such as date and manner in which the city (or town) was chartered, date and type of market establishment, and geographic coordinates. This paper will work largely with the data on town charters, which, in the authors’ own words, “necessarily remains a broad term” given the scale and scope of the Empire. [3]

The 23 Regions of the Städtebuch, with numbers corresponding to region_id value in the “Princes and Townspeople” dataset. Elbe river relevant later in this paper.

Murkiness aside, the field of study around the Holy Roman Empire’s political geography does not want for scholarship. A great deal of central European record survives from the medieval period onward. The German world itself has spent much of the 200 years since the HRE’s dissolution in the limelight, as a center of European political, economic, and military activity from the Council of Vienna in 1815 and Bismarck’s nationalist triumph in 1871, through both World Wars to the fall of the Berlin Wall. It is something of a truism that the degree of a country’s political significance to the US in the present leads rather directly to its degree of prominence in US academia; the decline of the study of Japanese history, and the rise of Chinese studies, both coincide with the trajectories those countries’ relative economic and political importance (or anticipation of such) to the US. While this rule may not be hard and fast, it nevertheless seems to apply to Germany, as medieval and early modern HRE studies boomed in the 19th and 20th centuries, but now find themselves overshadowed by studies of those nations, and themes, which appear more critical to the United States international position.[4]

However, studies of the Holy Roman Empire still find a place in academia. Peter H. Wilson’s Heart of Europe (2016), which forms the guidebook for this paper along with the University of Munich project, takes up the longue durée torch par excellence. Wilson covers major themes and trends in cultural and religious activity, economic development, geographical expansion, and political and diplomatic relations, all the while pushing back on claims in previous historiography both to the beneficence of the HRE’s civilizing mission and to the Empire’s immutable status as a deadweight on Europe and the German people.[5] There also exist many recent studies on the HRE—and some of its constituent organizations, like the Hanseatic League—as a potential model for the future of the European Union and more local European political partnerships. This argument often positions itself in response to the perceived failure of nationalism and the “nation-state” as humanist and progressive solutions to the age-old problem of human political strife.

It would be natural, then, to situate my project in such a legitimizing field as the current existential crisis of the European Union. But that is not the goal with which I have set out for this project, in large part due to my unfamiliarity with issues in the EU beyond surface-level political-philosophical debates. This project will be working mainly with data on city and market establishment in pre-capitalist and pre-democratic times, but I would like to use it as a precursor to understanding connections between the HRE and the EU. I have no doubt such a connection can be made, since the patterns of development and population shifts that I will attempt to divine in this project are a key part of the history of Germany’s political development—just as patterns of westward settlement and population “relocation” across the US or China still play key roles in each country’s recent and present issues.

For the purposes of this project, I will be looking at the establishment of towns and physical markets from the beginning of the reign of Otto I (r. 936-973) to the beginning of the Great Peasants’ Revolt (1524). I begin with Otto for two reasons; first, he centralized much of the power of the German kingdom and the broader HRE after more than a century of fragmentation and disarray in the wake of the death of the first formal Emperor, Charlemagne—and thus is regarded by many as the progenitor of what we now call the Holy Roman Empire. Secondly, a cursory look at the town charter data suggests the bulk of such charters occurred during this time period. In the words of the authors of the University of Munich study,

In the HRE, the establishment of cities overwhelmingly is a phenomenon of the 12th century onwards. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, cities and commercial centers did not play a prominent role in European societies. Self-sufficiency was a dominant form of sustaining needs, and [of sustaining] the agrarian sector… the European ruling class lived in fortresses in rural areas, which ainly [sic] had a military function and were seen as a way to protect land and people.[6]

Town charters, then, did not see their heyday until nearly two centuries after Otto’s coronation and the beginning of this study’s time frame; but, as we will see later on, town charters did occur before the 12th century (if in reduced number), and did follow certain significant patterns such as expansion eastward and northward.

The choice to end the study with the Great Peasants’ Revolt likewise follows two strains of reasoning; firstly, the Revolt took on an unprecedented scale of participation and violence that marked a new period of widespread social and religious upheaval, and that would come to redefine the final centuries of the Empire’s existence. Secondly, and quite relatedly, the Revolt makes a (but by no means the) convenient waypoint of the transfer of German and broader European society from domestic-focused economies and feudal land-based government, to models of broader international trade and absolutist consolidation of power. These are exceptionally simplistic terms with which to describe Europe’s economic revolution of the early modern period, but the Revolt provides a “good enough” outer bound for this study, which is primarily concerned with earlier periods.

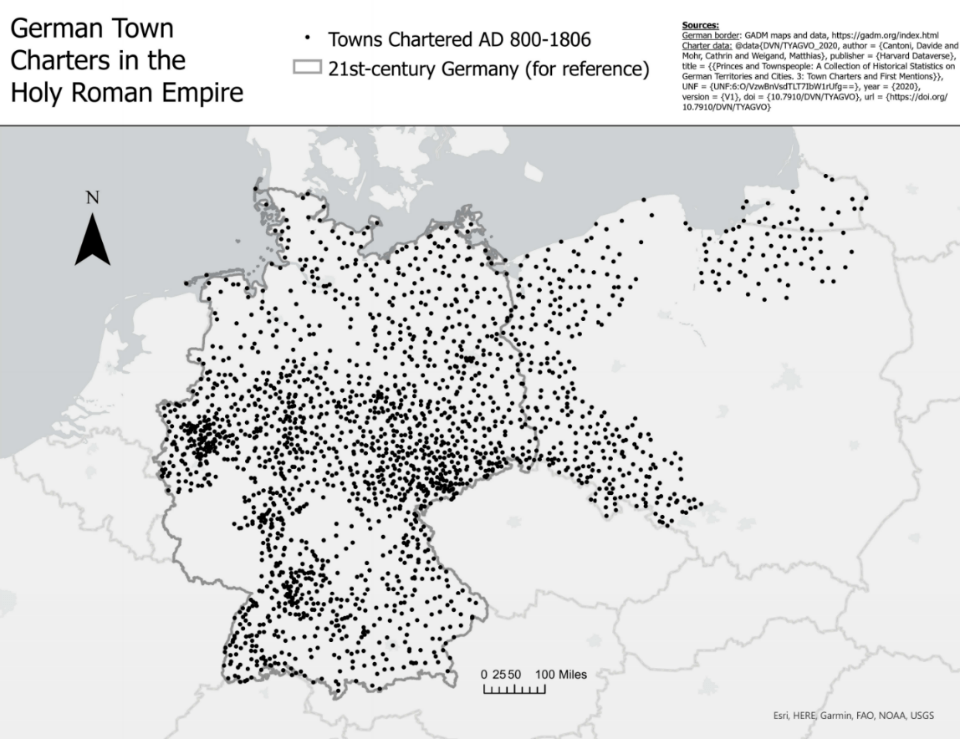

The first map (Figure 1) of this study locates all town charters and “first mentions” within the most extensive timeline of the Holy Roman Empire: 800-1806. This map mainly serves to acquaint the reader with overall settlement patterns before diving in to a narrower focus. Note the relative density of settlement in central Germany, from the Rhineland in the west to Saxony in the east, and the relative sparsity of settlement from Schleswig-Holstein to East Prussia in the north; the expansion of the Empire northeastward beginning in the 11th century, from the well-established heartland of Carolingian Germany into the historically Slavic- or Scandinavian-controlled lands along the Baltic coast, forms one of the main foci of this study.[7]

This map also gives an opportunity to point out the importance of historical context in looking at data, and what data this study lacks. The authors of the Deutsches Städtebuch only recorded cities within the confines of 1937 Germany; conspicuously missing are settlements within Czech lands (Bohemia in the HRE), northern Italy,[8] southwest Germany in the areas of Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate, and Austria. However, as this paper focuses largely on the north, such lapses do not prevent an interesting study. The only glaring “blank space” in northern data lies in West Prussia, between East Prussia and Pomerania—but the entire Prussian region held at best an informal status within the HRE during our medieval time period. West Prussia specifically changed hands a number of times between Poland and the eastward-oriented Teutonic Order; Poland gained full control of the region for nearly two centuries after their victory over the Order at Grunwald, and the subsequent Peace of Thorn.[9]

Figure 1

More importantly to note, the original author and progenitor of the Städtebuch, Erich Keyser, was a bona fide Nazi—before, during, and after World War 2. As I am a descendant of German Jewish refugees of the Nazi state, I would like to place my study firmly in an antiracist space, even if it does not deal with Keyser’s politics as a main theme. This also forms a good case study of Mark Trachtenberg’s injunction that facts never speak for themselves.[10] Simply because the names “data” and “data science” are applied to Keyser’s work and the “Princes and Townspeople” datasets, these records are not removed from the obligation of scholarly and ethical scrutiny. Furthermore, mere days before turning in this project, I received an email response from “Princes and Townspeople” authors Matthias Weigand and Davide Cantoni, who advised particular caution in dealing with Keyser’s data on Prussia and Slavic areas. The Städtebuch may be a valuable resource, but it is a product of a fascist, ethnic-cleansing intellectual space; and throughout this paper, questions of its motivations, inclusions, and exclusions should never leave the mind of the reader.[11]

The second map (Figure 2) visualizes all charters within this paper’s next chronological narrowing, 936-1525. A cursory look reveals there is little apparent difference in point density between the two. This is not a trick of the eye; of the 3,993 town charters that occurred within the HRE’s 1000-year existence, 85% (3,410 charters) fall within the 600-year period of this study.

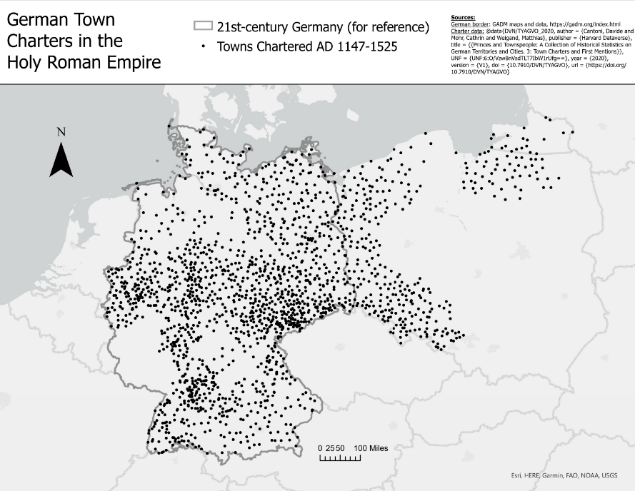

The third map (Figure 3) narrows the view even further, showing that in the 378 years between the beginning of the Wendish Crusade[12] (1147) and 1525—only 38% of the Empire’s chronological existence[13]—one finds 70% (2829) of the original set of 3993 charters. While some milder local peaks in settlement occurred before and after this four-century period, the HRE experienced an absolute maximum of expansion and settlement in these centuries. Similar patterns emerge from all three maps, with most settlement density falling within the triangular area between Westphalia in the west, Saxony in the east, and Württemberg in the south. Let us now turn to a look more directly at change over time.

Figure 2

Figure 3

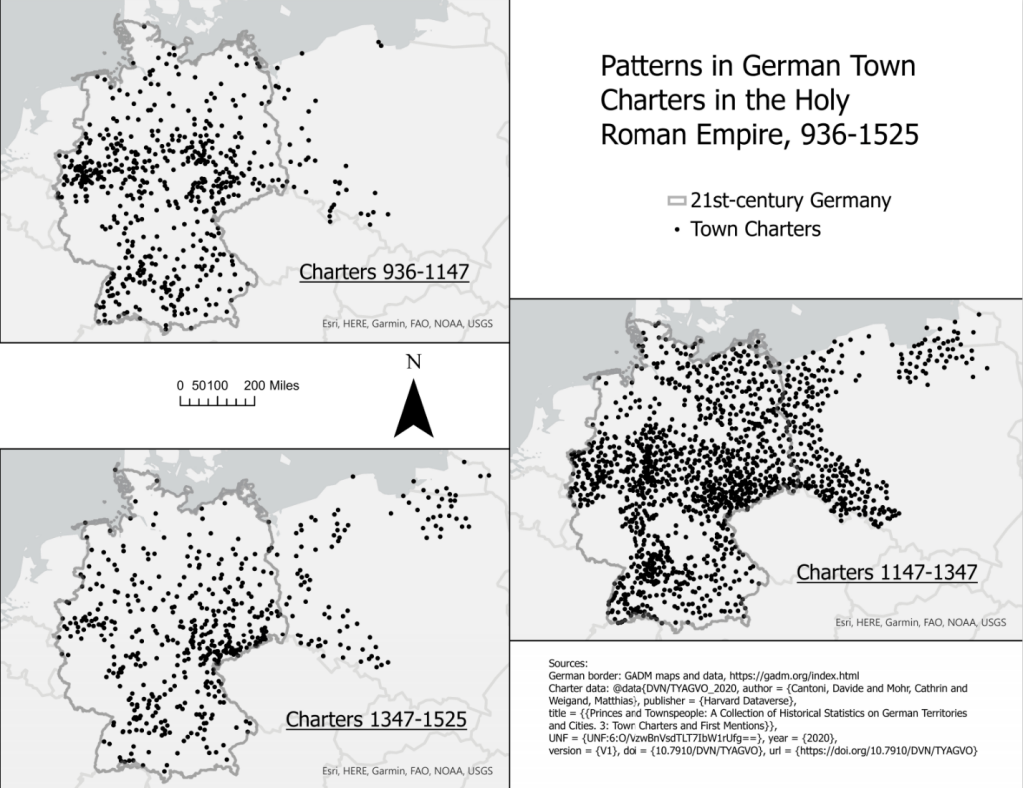

From prior knowledge about the effects of the bubonic plague on European populations in the 14th century, I hypothesized that dividing our period up using the approximate date of the plague (1347) might reveal more obvious patterns in at least the total number of settlements. For this next map series (Figure 4), I divided our broader period into three better-defined sections of time, with the middle section bound by the Wendish Crusade[14] at the beginning and the advent of the Black Death in Europe at the end. This division reveals a rather pronounced boom-and-bust cycle. While a relatively tame 500 and 622 charters occurred in the first and third sections (respectively), an astronomical 2214 charters occurred in the two centuries between the Crusade and the Plague. That is, 50% of all charters in the thousand-year duration of the HRE emerge in one-fifth of the time.

Figure 4

A couple more localized patterns emerge from this series as well. Firstly, of the 1147-1347 section, 903 of the 2214 charters occurred within regions[15] historically dominated by Slavic peoples—that is, from west to east, Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg, Brandenburg, Pomerania (Pommern and Hinterpommern), Silesia (Schlesien), and East Prussia (Ostpreußen). This is an enormous statistic, and I would like to address potential causes for the sheer weight of settlement in these “new” areas slightly later on in the paper.

Secondly, while settlements exploded in previously non-German areas, the map reveals a few “hot zones” of extreme density in “old” German lands. These zones, comprising 5 of the remaining 15 regions and 673 of the remaining 1107 charters, fall primarily in Rhineland and Westphalia in the west, Hesse in the center, Saxony in the east-center, and North Württemberg in the south—the triangular heartland area previously mentioned. Why these specific areas received such focus of the population, and why sparsely chartered regions like Lower Saxony in the northwest or Bavaria in the southeast did not, will also be addressed with secondary source literature later on in this paper.

The expansion northeastwards in the 12th century came from a complex set of directives and motivations, not the least because of its formal association with the broader Second Crusade of 1147. As for the initial inspirations for the Crusade, the idea for Christianization efforts against the pagan Slavs of the Baltic coast was a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario between German princes and the pope. However, the Crusade did not only attract the attention and resources of HRE constituents; in fact, various Christian Slavic and Scandinavian peoples also joined their own Christianization movements with the HRE. [16] Thus, in their concentrated and violent ventures into Wendish territory in the 1140s, the Germans found themselves accompanied by a rather geographically diverse cast of militants. In the words of Peter Wilson, author of Heart of Europe,

The initiative lay with count Adolf II of Holstein, who began by evicting Slavs from Wagria [in northeastern Holstein] and replacing them with Flemish and German settlers. Official sanction as a crusade attracted Germans, Danes, Poles, and some Bohemians to Adolf’s army, allowing him to greatly expand operations. ‘Indulgences on this front could be won at a lower cost and in a fraction of the time necessary to complete a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.’ The cooperation of the Polish and Pomeranian dukes proved crucial to success.[17]

Even before a discussion of deeper economic and political issues in the area, military operations on the Baltic coast evidently held great value to groups from the cardinal extremes of the Holy Roman Empire, from Flanders in the west to Bohemia and Poland in the east, and from Denmark in the north to the pope (whose involvement in such a war is perhaps the easiest explained, as the papacy became at least rhetorically implicated in most conflicts between Catholics and non-Catholic peoples across Europe). The crusade in the north became permanent by papal doctrine a century after the original Wendish conquest; more on this later.[18]

But despite its formality as a crusade, the wars and resultant German settlement in Wendish lands at this time drew participants with often a collection of often more informal motivations. This informality, with respect to the auspices of the Holy Roman Imperial structure and prerogative, came to define the Empire’s general approach to the Baltic coast. “The emperor,” Wilson continues, “was hardly involved in either colonization or the Northern Crusades… although Frederick the II [r. of Germany 1212-1250] issued his own authorization to the Teutonic Knights, the Order active independently in carving out its own state.”[19] Perhaps the issue here was timing; as much of the rest of west-central Europe involved itself in the wars occurring in the Levant, one can hypothesize that the call of the northern efforts appealed to those groups either geographically proximate to the region, or low enough on the political hierarchy to benefit from that crusade which was by its nature secondary—it is doubtful that the Holy Roman Emperors was as concerned with the prestige of fighting the Wends as they were with the prestige of reclaiming the Holy Land from Islamic forces. Without dragging myself or the reader into a discussion of the complex sociopolitical motivations for individual participation in crusading and related activities, it at least appears that the sheer force of the Christian push against the Wendish peoples drew much of its weight from the immediacy of social gain and political convenience—for more distant soldiers and for nearby princes—that such an activity promised.

However, although fundamentally violent and often “informal,” rampant expansion into the historically Slavic areas of the Wendish crusade often was not haphazard. Before looking deeper at the nature of population expansion northeastward, it is necessary to briefly return to a discussion of the Deutsches Städtebuch. For its part, the Städtebuch record works largely with towns chartered by German peoples—as Alexander Pinwinkler argues in his chapter in German Scholars and Ethnic Cleansing, 1919-1945 (2005), one of Keyser’s broader goals as a Nazi historian was to argue that civilization did not exist in these parts of central Europe until Germans brought it there.[20] It seems likely to me that the Städtebuch would thus leave out many records of previous Slavic settlements—but it does not leave them all out; a number of datapoints do exist for the existence of prior Slavic settlements at the sites of later German towns. For example, an entry in the “Princes and Townspeople” data exists for Lübeck in the year 1000 which reads, “Ein wend. Ort Lubeke lag nahe [sic] der Einmündung der Schwartau in die Trabe[sic], 4km unterhalb der heutigen Stadt— “a Wendish place Lubeke lay near the confluence of the Schwartau [river] in the Trave [river], 4km south of today’s city.”[21] This is perhaps small consolation, but consolation nonetheless that the Städtebuch does not constitute a complete obfuscation of the Slavic record.

Beyond this, however, Keyser and his team also did not fabricate the relative general sparsity of settlement along the Baltic coast before the mid-12th century; the Baltic lands were not nearly as densely settled under primarily Wendish occupation as they become during the settlement explosion after the Wendish crusade. Once the first German lords conquered the area after the crusade, they began encouraging an influx of “known entities” into the lands from which they had recently expelled or suppressed Slavic populations. In the words of Michael North, author of The Baltic (2015, trans. Kenneth Konenberg)

Like most of the regions of eastern central Europe, the southern and eastern coasts of the Baltic were greatly influenced by German settlement. This form of development was a result of the low population density in many regions. Landlords competed for the availability and services of peasants and therefore supported settlement in their lands in order to increase their income. Security probably also played a role because they feared Slavic uprisings and those of the pagan population, which they hoped to counter by settling German peasants on the land.[22]

Regardless of any bogus metric of the extent of “civilization” in these Slavic lands before German arrival, these lands nevertheless were not dense population centers a priori. Many Wends and other non-HRE Slavic peoples evidently remained, the influx of German lords into lands which—from an economic development perspective—did not have sufficient population to maintain the German lords’ desired agricultural production. This created a self-fulfilling cycle of settler-colonialism in which (familiar to those of us in non-subsistence-based market societies in the 21st century) initial economic and population expansion required further economic and population expansion to sustain itself. However, that the princes feared for their security also suggests that, while the Wendish lands may have been relatively sparsely settled compared to older German regions, enough peoples occupied those lands (or survived the German conquest) to remain a substantial threat. Although this does not explain the particular motivations of the German peasants in moving to these areas, it does address the top-down demand of the princes for settlement as a method of economically and politically securing their newly-conquered holdings.

The crusades in the north also did not end with the conquering of Wendish lands in the mid-12th century. In fact, the main German organization[23] that would dominate the northern crusades for the next four centuries—the Teutonic Order (officially Orden der Brüder vom Deutschen Haus der Heiligen Maria in Jerusalem)—originated during the Third Crusade in the 1190s, and only arrived in force on the Baltic coast in 1238.[24] As the main overlords of the Baltic regions from eastern Pomerania (Hinterpommern) through East Prussia, and at times beyond, the Order was the organization responsible for keeping those regions’ ties to the Holy Roman Empire at the level of informality discussed on page 5 of this paper. After conquering and converting the lands and peoples of the southern Baltic coast, the Order continued to legitimize its existence as a crusading organization via its aims to convert the grand duchy of Lithuania. In Peter Wilson’s words, “Pope Innocent IV had been persuaded to proclaim a permanent Baltic crusade in 1245, legitimizing regular recruitment for the Teutonic Order.”[25] I contend, however, that the Order drew from its “Christian mission” the legitimacy not only of its recruitment but of its fundamental maintenance as a political state; such a reading is encouraged by its decline after the conversion of Lithuania to Roman Catholicism in 1386.[26] Even before the Lithuanian Prince Jagiełło’s (Jogaila) conversion in that year, the Order had already included in its mission the conversion of the pagan Samogitians in the northeast periphery of its own and Lithuanian lands. However, this mission proved military difficult for the Teutonic Knights, and Polish-Lithuanian sponsorship of the Samogitian military formed one of the most apparent reasons for the Order’s protracted downfall in the 15th century.

But as the earlier maps show, the number of town charters experienced a meteoric rise across Germany in the middle period of this study, with just over half of the total charters occurring within older German lands. Ulla Kypta et al. affirm the eastward expansion patterns and address the broader settlement explosion in Methods in Premodern Economic History:

Because of the warmer climate after c. 1050, agricultural productivity increased noticeably, and by colonization as well as by eastern-bound migration, a larger amount of arable land could be used for the production of agricultural goods. Both factors contributed to a sustained population growth, and together with the foundation of hundreds of towns and a sustained economic growth resulting from this, they formed the socio-economic background of what has to be considered a significant societal take-off.[27]

Climatologically, then, German populations were positioned for a take-off (and already experiencing its early stages) at the time of the Wendish Crusade in 1147. Furthermore, European farmers began to practice the substantially more efficient system three-field farming system in this period, which, along with the simultaneous growth of the European market and trade economy, would have made crop yields higher, more reliable, and more transferrable across geography.[28] All of these factors would already have facilitated growth in Germany south of the Wendish regions, but expansion into the northeast meant more land on which to grow more food, which in turn was marketable across the German space (and more broadly across Europe).[29] Many of the towns settled or resettled in the north by German invaders and peasants after the Wendish Crusade in fact were initially chartered with or soon adopted the Lübeck law, which situated much of the towns’ economic and political power with an interregional class of “long distance merchants.” [30]

As discussed previously, the lords of these newly German-occupied regions found themselves with a lot of land and a dearth of laborers to work it (and apparently, traders to maximize the efficiency of its surplus), and thus actively worked to draw new settlers into their lands. The privileges they granted were quite substantial; North notes that “as an incentive, German [colonists] were given larger farms and guaranteed hereditary rights of use, personal freedom, and the right to administer their own villages as well as freedom from services and rents during the initial period of settlement.”[31]

Let us return now to the patterns in town charter data. I hypothesized earlier in the paper that the rather overtly settler-colonialist arc of German expansion into the regions of the south Baltic coast would correlate with a greater level of informality and/or poorer official documentation of town charters in those regions. I drew this hypothesis from my knowledge of other major settler-colonialist projects with which I am familiar, like Russian settlement east of the Muscovite heartland, or American or Chinese settlement of each country’s respective “wild west” in the 18th and 19th centuries. My assumption was that the further one goes from the territorial core—because the Baltic coast was indeed quite far from the core of imperial concern[32]—the more likely it would be that towns in previously unsettled or de-settled lands would have been chartered without direct legal permission or intervention from governing bodies. To my surprise, the “Princes and Townspeople” data only shows a minor trend of this sort.

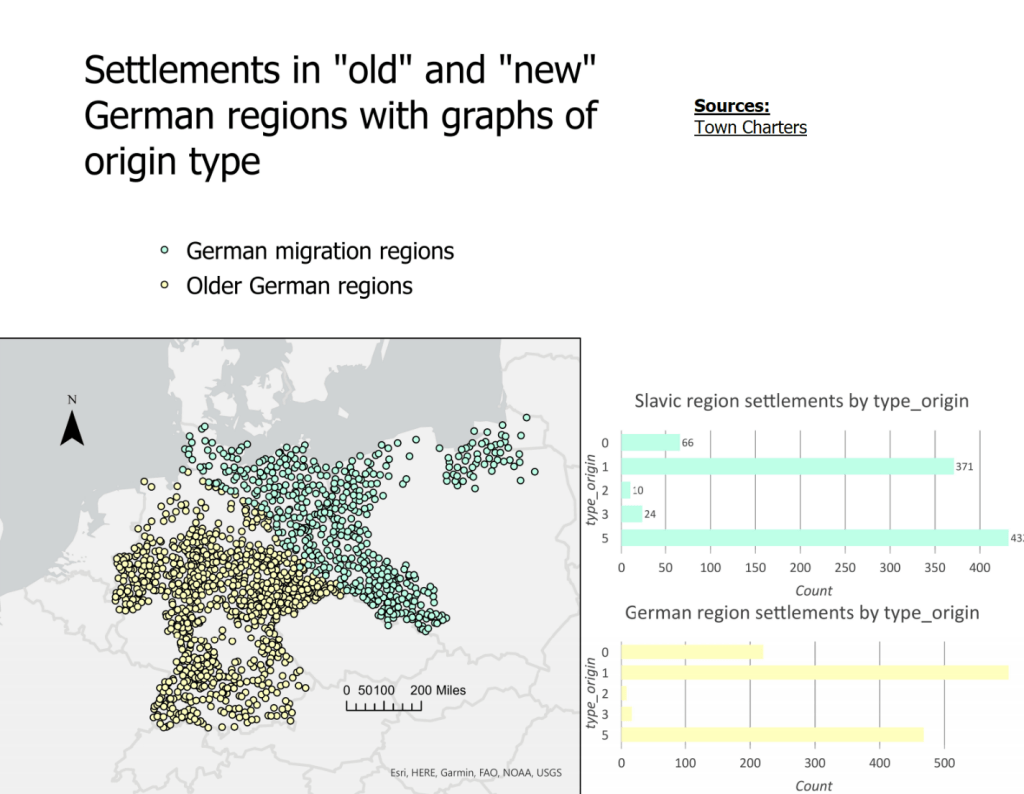

As previously mentioned, every town entry in the “Princes and Townspeople” dataset includes variables on a broadly defined type of charter. Addressed here will be the “type_origin” variable, which the authors call the “broad category of city development.”[33] This variable has six possible categories: 0) Evidence of city character prior to town charter, 1) Formal bestowal of town charter, 3) Withdrawal of town charter, 3) Changes to town charter, 4) No information on town charter, 5) First recorded mention of a settlement. As this list suggestions, many records of towns and their chronology exist only indirectly, with first mentions and prior evidence filling in where no formal legal documentation exists (or ever existed). To me, first mention appears to be the most legally informal category short of complete lack of written documentation (categories 0 and 5) From the map of all towns 1147-1347, I have isolated those towns within the eight regions of the Wendish Crusade (Hamburg in the west to East Prussia in the east); I then graphed the number of entries in each category on a bar chart. I also graphed the same for other 15 regions 1147-1347 set for comparison (Figure 5). Evidently, “formal bestowal of town charter” and “first recorded mention of a settlement” are overwhelmingly the most common charter forms in this period (the two categories together composing 544 of the 597 entries in the northern regions, and 1870/2214 in the entire Städtebuch area) with a moderate number of category 0 and minimal entries in the other categories.

Figure 5

A comparison between the two graphs reveals mild but not overwhelming differences. In the historically Slavic regions, category 1 “formal bestowals of town charters” make up 41% (371/903) of all records, while 48% (432/903) of the record comprises category 5 “first recorded mention of a settlement.” In the historically German regions, 46% of town records fall into category 1, while only 36% fall into category 5. Although these statistics do by small measure confirm my hypothesis, I had expected more differentiation between the two regions than 5% difference in category 1 and 12% in category 5. Inexperienced in statistics work as I am, though, the Slavic regions’ 12% lead in category 5 settlements does seem statistically significant if not explosive. Furthermore, “first recorded mention” is a rather broad phrase, and, with additional and more fluent historiographical analysis of the Städtebuch and the recent “Princes and Townspeople” project, perhaps greater nuance could be teased out of these numbers.

The biggest jump actually lay in the number of category 0 “evidence of city character prior to town charter.” The old German regions had three times the percentage of town instances (22%, or 286/1311 settlements) recorded based on prior and undocumented evidence of city existence than in the Slavic regions (7%, or 66/903 settlements). This suggests either a larger concentration of historically settled land in the German heartland than the relatively sparsely occupied Baltic coast, or a greater desire in German settlers to found new cities rather than settle on old ones (which would have previously been occupied by non-Germanic peoples). Or, potentially, it represents a choice on the part of the Städtebuch authors to leave out mention of many previous Slavic settlements in order to bolster the narrative that civilization only arrived with the Germans. A discussion with the “Princes and Townspeople” authors here could shed great light on this question. However, Peter Wilson does excellently summarize related propagandist tendencies in pre-WWII German historiography:

Acutely aware that Germany had lost out in the [19th-century] European scramble to steal other peoples’ lands, nineteenth-century historians adopted the language of high imperialism to present this migration [of Germans east and northeastward] as a legitimate ‘drive to the east’ (Drang nach Osten) to colonize ‘virgin land’ and spread a supposedly superior culture. In fact, eastwards migration was part of a much wider movement of peoples through the Empire, which included forest clearance, marsh drainage, land reclamation and urbanization, all frequently in areas already viewed as ‘settled.’[34]

As to who exactly had already viewed these areas as “settled” is unclear to me from Wilson’s writings; were they viewed by their previous inhabitants (Slavic peoples) as settled, or did even the colonizing Germans view their new lands as settled? Regardless, according to Wilson, “400,000 people crossed the Elbe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, causing an eightfold increase in the population of the region immediately beyond.”[35]

I draw a couple of conclusions from this project. Firstly, the initial lead I followed at the outset, that the middle ages witnessed a rather substantial ebb and flow of town settlement, turned out to be quite fruitful. The trends suggested by the data collected within the “Princes and Townspeople” dataset, from the Deutsches Städtebuch and beyond, are broadly corroborated by the historiography. Not only did the borders of the German-controlled world expand rapidly and extensively northeastward in the 12th-century onward; this expansion also accompanied a broader explosion in population and settlement numbers in all German-controlled regions and beyond. As I also suspected, the arrival of the Plague in Europe sounded the death knell for this growth, as “the total number of German settlements fell [emphasis mine] by 40,000 to 130,000 across 1340-1470.”[36]

Finally, uncountable hours of GIS work revealed a complexity to the history of the trans-Elbe regions of Baltic Germany and beyond that long went under my radar as an American student of history. This project was never meant to be a neatly wrapped or well-contained analysis of the political geography of the Holy Roman Empire, Germany, or the south Baltic coast. Rather, I took it as an opportunity to process the broader history of the HRE and to get a “foot in the door” of a number of different topics that interest me—the geopolitical evolution of the HRE writ large, the Northern Crusades, the political economy of northern Germany, the relationship of the Teutonic Order to the Prussian region and to the Empire, and the early days of the Hanseatic League (which I never got to in this paper). I hold all of these as potential topics for my master’s thesis, which will inevitably have to take a much more zoomed-in look at whatever macrocosm of Central European history I choose. I may not be a data scientist or an expert in quantitative analysis, but I believe the inordinate amount of time I spent working with the GIS turned this project from a literature review to a nuanced and creative exercise. And despite the relative simplicity of the operations that I performed in the GIS, I would not have been able to efficiently visualize these trends and provide potential direction for new insights without the tools in the 21st-century geographic historian’s toolbox. I look forward to returning to this work, and this area of history, in the future.

Bibliography:

Bayley, C.C. “The Holy Roman Empire.” Speculum 45, no. 1 (1970). https://doi.org/10.2307/2856001.

Berghahn, Volker. “Germany: A New Social and Economic History, Vol. 3.” European History Quarterly 35, no. 2 (2005). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/026569140503500219.

Bogucka, Edyta, Davide Cantoni, and Matthias Weigand. “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 1: City Locations and Border Maps.” Harvard Dataverse, 2019. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/ZGSJED.

Cantoni, Davide, Cathrin Mohr, and Matthias Weigand. “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 3: Town Charters and First Mentions.” Harvard Dataverse, 2020. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TYAGVO.

Haar, Ingo, and Michael Fahlbusch. German Scholars and Ethnic Cleansing, 1919-1945. New York: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Heer, Friedrich. The Holy Roman Empire. London: Orion House, 1995.

Kļaviņš, Kaspars. “The Ideology of Christianity and Pagan Practice among the Teutonic Knights: The Case of the Baltic Region.” Journal of Baltic Studies 37, no. 3 (2006). http://www.jstor.org/stable/43212723.

Kypta, Ulla, Julia Bruch, and Tanja Skambraks. Methods in Premodern Economic History Case Studies from the Holy Roman Empire, C.1300-c.1600. Springer International Publishing, 2019.

North, Michael. The Baltic: A History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Scribner, Bob. Germany: A New Social and Economic History, 1450-1630. Vol. 1. 3 vols. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Urban, William. “The Teutonic Knights and Baltic Chivalry.” The Historian 56, no. 3 (1994). http://www.jstor.org/stable/24448704.

Wilson, Peter. Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

[1] Particularly regarding the northern European trading league, the Hanse, about which I originally intended to write this paper.

[2] But politically complicated, more on this later.

[3] Davide Cantoni, Cathrin Mohr, and Matthias Weigand, “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 3: Town Charters and First Mentions” (Harvard Dataverse, 2020), https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TYAGVO. 2

[4] I derive this claim from many conversations with professors in the field at such universities as the University of Chicago, the University of Maryland, and Columbia University.

[5] Peter Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016). Many 19th-century historians argued that the empire had prevented Germany from experiencing the same “natural” arc of centralization and national definition as many of its European contemporaries. Wilson addresses this at many points in his book, such as on page 3.

[6] Cantoni, Mohr, and Weigand, “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 3: Town Charters and First Mentions.” 2-3

[7] They were responding to an email I sent earlier, in which I inquired on their thoughts on Keyser’s Naziism and its effects on their project.

[8] Which itself had a confused and poorly defined relationship to the imperial core anyway

[9] Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. 209-210

[10] Trachtenberg, Marc. The Craft of International History: A Guide to Method. PRINCETON; OXFORD: Princeton University Press, 2006. Accessed December 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7rnfc.

[11] Once again, a valuable lesson in checking the sources of your sources.

[12] Discussed later

[13] 43% if one places the HRE’s beginning at Otto’s ascendance

[14] By members of the HRE against the pagan Slavic populations northeast of the Elbe river. This crusade is defined in greater detail later on in the paper.

[15] Edyta Bogucka, Davide Cantoni, and Matthias Weigand, “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 1: City Locations and Border Maps” (Harvard Dataverse, 2019), https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/ZGSJED. I take these region categories from the 23 regions categorized in the Städtebuch, outlined by the University of Munich authors

[16] Michael North, The Baltic: A History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015). 34

[17] Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. 98

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Alexander Pinwinkler, “Volk, Bevölkerung, Rasse, and Raum: Erich Keyser’s Ambiguous Concept of a German History of Population, ca. 1918–1955,” in eds. Ingo Haar and Michael Fahlbusch, German Scholars and Ethnic Cleansing, 1919-1945 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2005).

[21] Cantoni, Mohr, and Weigand, “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 3: Town Charters and First Mentions.”

[22] North, The Baltic: A History. 40

[23] But not the first Germanic Christian order in northeast Europe; the Livonian Order of the Swordbrothers had already set up a substantial by the early 13th century, and their defeat at the hands of the native occupants of Livonia in 1237 formed the impetus for the Teutonic Knights’ relocation to the area. Kļaviņš, “The Ideology of Christianity and Pagan Practice among the Teutonic Knights: The Case of the Baltic Region,” Journal of Baltic Studies 37, no. 3 (2006), http://www.jstor.org/stable/43212723.

[24] William Urban, “The Teutonic Knights and Baltic Chivalry,” The Historian 56, no. 3 (1994), http://www.jstor.org/stable/24448704.

[25] Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. 98

[26] See William Urban, “The Teutonic Knights and Baltic Chivalry,” and Kaspars Kļaviņš, “The Ideology of Christianity and Pagan Practice among the Teutonic Knights: The Case of the Baltic Region.” Urban’s research on the area is valuable but, as Kļaviņš correctly points out, Urban takes a rather pro-German approach which should give the reader caution

[27] Ulla Kypta, Julia Bruch, and Tanja Skambraks, Methods in Premodern Economic History Case Studies from the Holy Roman Empire, C.1300-c.1600 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). 20

[28] Bob Scribner, Germany: A New Social and Economic History, 1450-1630, vol. 1, 3 vols. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996). 1-3

[29] Ibid.

[30] North, The Baltic: A History. 45

[31] North. 40

[32] Wilson. 98

[33] Cantoni, Mohr, and Weigand, “Princes and Townspeople: A Collection of Historical Statistics on German Territories and Cities. 3: Town Charters and First Mentions.” 4

[34] Wilson. 95

[35] Ibid.

[36] Wilson, 507

Aidan Lilienfeld, for “Spatial History and Historical GIS” Columbia University, December 2020