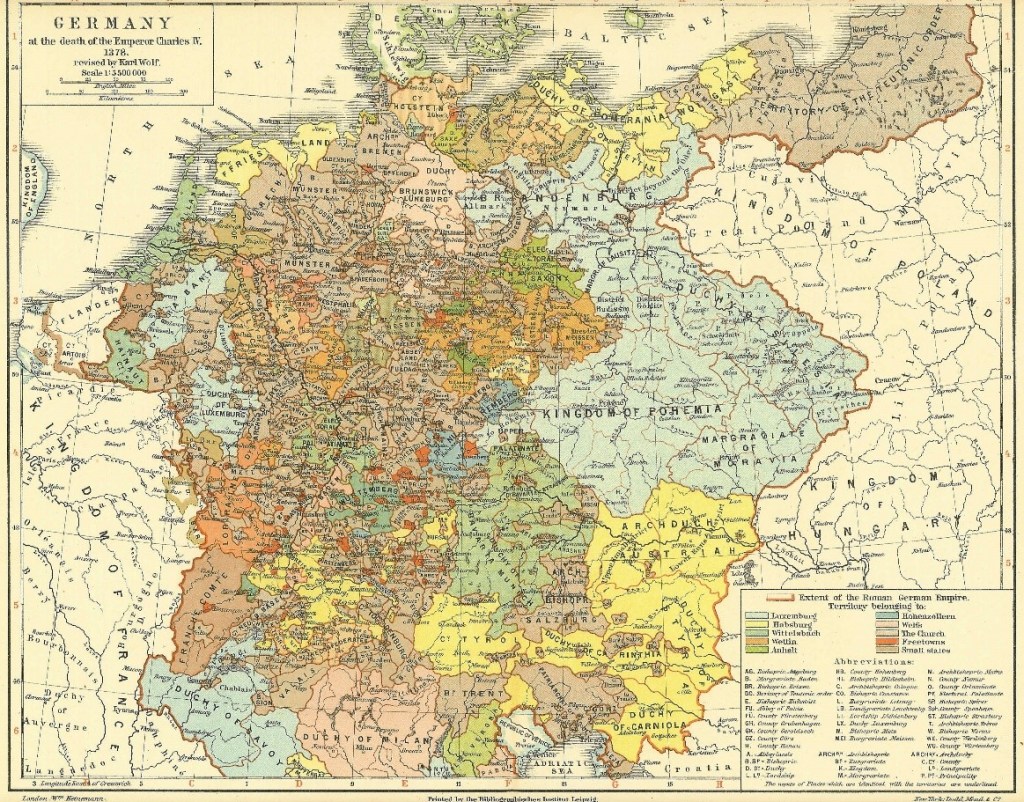

In this paper, I will look at the map “Germany at the death of Emperor Charles IV, 1378,” which was created for Volume 7 of Hans Ferdinand Helmolt’s The History of the World; A Survey of a Man’s Record, published in 1902. Helmolt (d. 1929) was a German historian and political thinker around the turn of the 20th century.[1] He also wrote monographs on such figures as Frederick the Great of Prussia and Otto von Bismarck—and, later on, he was a proponent of the German nationalist Kriegsschuldlüge philosophy, which denied German responsibility for World War I. This philosophy greatly contributed to the meteoric rise of Naziism in German only a few years after the war.

Helmolt makes his pro-German bias quite apparent on this map. The map’s title asserts that what is visualized within is “Germany,” at the death of the Emperor Charles IV (1378). Already, the conflict of nomenclature comes to the fore – Charles IV was the Holy Roman emperor, the lands of which Germany was only one constituent kingdom. Often confused for each other, the Holy Roman Empire (HRE, for short) is not in fact synonymous with the German Kingdom; the HRE covered much of Central Europe and, beyond German-speaking-majority lands, also included the kingdoms of Bohemia, Moravia, Italy, and other non-German regions such as the Low Countries.

Next, let us look at further cases. The Kingdom of Bohemia was very much a part of the Holy Roman Empire, but it was not German nor “Germany”; as a Slavic-speaking-majority kingdom, it operated distinctly from the German Kingdom in this time. Helmolt includes Bohemia, correctly, within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire in this map. He also includes (correctly) many northern Italian states, and Low Countries states, within the HRE border. Why, then, is this map not titled “The Holy Roman Empire at the death of Emperor Charles IV, 1378”?

I argue that Helmolt chose to title this map Germany, and not the Holy Roman Empire, for political reasons. On the historiography of German representation of “their lands, particularly in the east, Peter Wilson states:

“Acutely aware that Germany had lost out in the [19th-century] European scramble to steal other peoples’ lands, nineteenth-century historians adopted the language of high imperialism to present this migration [of Germans east and northeastward] as a legitimate ‘drive to the east’ (Drang nach Osten) to colonize ‘virgin land’ and spread a supposedly superior culture.” [5]

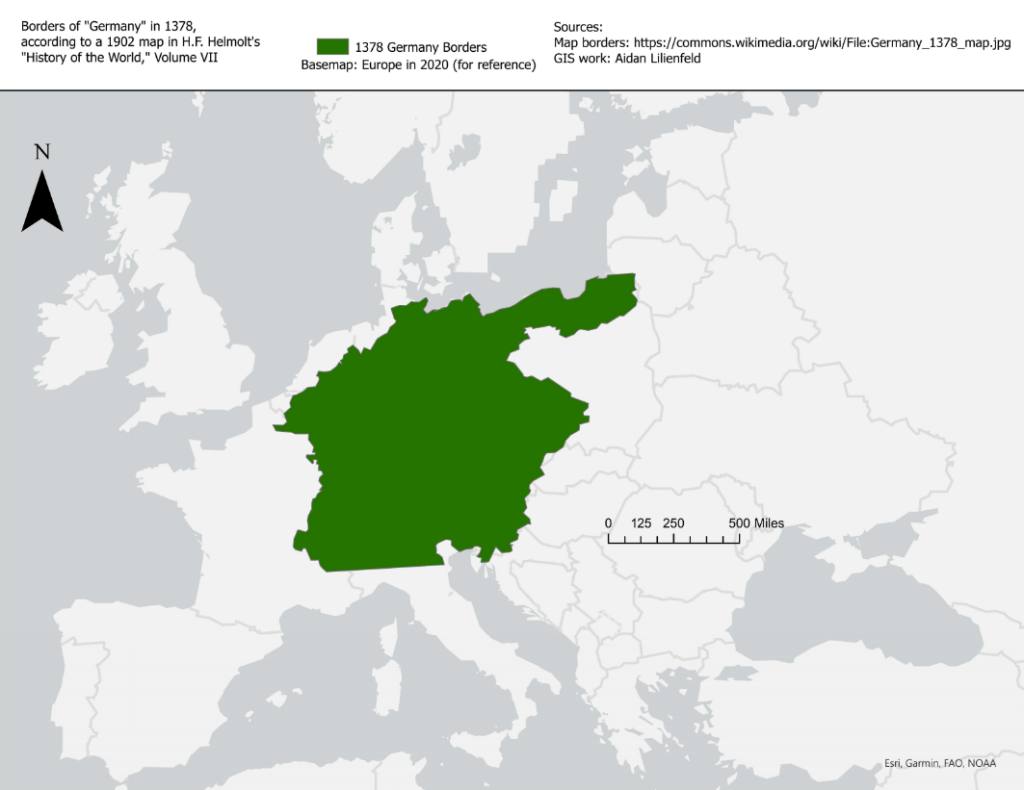

But this argument extends well beyond Wilson’s own. Although the name “Central Europe” (Mitteleuropa in German) does not appear on Helmolt’s map, the region the map shows is nevertheless quintessentially Central European. As Alexei Miller argues, the concept of “Central Europe” only emerged in the 19th century, and largely of German construction.[6] In A Global Transformation of Time, Vanessa Ogle also argues that Mitteleuropa formed a specific rhetorical tool for German statesmen Helmuth von Moltke and Otto von Bismarck, in their post-unification designs for the German Reich.[7] Once these Reich strategists had successfully united the disparate German principalities under one national flag in 1871, they went on to argue that Germany in fact held a de jure claim as protector, guarantor, or overlord of all of Mitteleuropa.

In titling the above map Germany, I argue then that Helmolt was not simply confusing names but was in fact combining historical German and Holy Roman Imperial claims to support the Bismarckian/post-Bismarckian claim that Germany had rights to all other lands colored in on this map which had once, by one name or another, belonged to a German Emperor. Prussia, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, perhaps even Italy—Helmolt likely saw these lands as rightfully, if not presently, German. Thus, we see most of Central Europe colored in as Germany on his map. These very designs, drawing their legacies from the German push eastward in the middle ages, went on to form one of the fundamental tenets of Nazi geopolitical ideology.

This map then puts us in Central Europe in two different times: the late medieval period of the Holy Roman Empire, and the modern period of the Second Reich. It is interesting to think about the wildly different political structures of “Germany” in these two times; in 1378, the German Holy Roman Empire provides perhaps the quintessential example of medieval sociopolitical decentralization. Many German scholars have argued since the fall of the Empire in 1806, the Empire was so anti-nationalist in its construction that it hindered Germany from developing on the same path of modernism as its European neighbors like France and England. I believe this idea relates directly to the work of my colleague Shreya, who studied a map of France in the 15th century at that kingdom’s moment of proto-national formation/centralization. It is interesting to note that in this same period of fragmentation in the Empire, France began to centralize as the state that we now know.

This map also relates to the work of my colleagues Hanbyeol and Matthew, both of whom looked at Europe much later on: Matthew, Central Europe in the 18th century, and Hanbyeol, Italy in the 19th. The beginnings of the German nation were already taking place in the 18th century with the rise of the kingdom of Prussia—a kingdom which, despite its place in the fragmented HRE, later went on to form Germany in the modern period under Otto von Bismarck and other statesmen. Hanbyeol’s study of Italy, likewise, gets to the political challenges that nationalist state-makers experienced in the 19th century. Germany and Italy both entered that century highly decentralized, and exited it as “coherent” (by our 21st century standards) nation states. The process of centralization involves many steps, and whether in Germany or Italy, also involves particular forcefulness from one fragment of the old decentralized state. After all, history would show (in France, Italy, or Germany) that autonomous polities tend not to give up their autonomy unless coerced into doing so by a threatening power. In the Central European cases, those powers were often one fragment of the decentralized whole. In the German case, that fragment was Prussia; that fragment came to unify the “whole,” through a combination of war-making, diplomacy, and statecraft. And in this map, we see a German nationalist’s desire to claim not just German speaking lands, but much of Central Europe, as a further extension of the unifying project.

Bibliography:

“Helmolt, Hans Ferdinand.” Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e.V. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://saebi.isgv.de/biografie/Hans%20Ferdinand%20Helmolt%20(1865-1929).

Miller, Alexei, “Central Europe: A tool for historians or a political concept?”, European Review of History, 1999 Vol 6, No. 1.

Ogle, Vanessa. The Global Transformation of Time, 1870–1950. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Wilson, Peter. Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Map source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Germany_1378_map.jpg

[1] “Helmolt Hans Ferdinand.” Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e.V. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://saebi.isgv.de/biografie/Hans%20Ferdinand%20Helmolt%20(1865-1929).

[2] Per the map’s legend, colored in as part of the HRE, or “German Roman Empire, as Helmolt calls it. The fact that he calls it the “German” and not “Holy” Roman Empire is also worthy of further analysis, but this paper is too short to get into a further explanation of naming conventions around the Empire. Nevertheless, I imagine it is not a coincidence that he takes this opportunity again to imply to the viewer that the HRE was a fundamentally German institution.

[3] Emperor in the early 13th century

[4] Peter Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire, (Cambridge: Belknap, 2016), 98.

[5] Wilson, Heart of Europe,95

[6] Alexei Miller, “Central Europe: A tool for historians or a political concept?”, European Review of History, 1999 Vol 6, No. 1, 86.

[7] Vanessa Ogle, The Global Transformation of Time, 1870–1950, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2015, Ogle, 2.

Aidan Lilienfeld, for “The Idea of Europe” at Columbia University, February 2021